| Please note, there is currently no data to suggest extrafine formulations provide additional clinical benefit in comparison to non-extrafine formulations.2,11 |

In this article, we’ll explore in detail the small airways – their role within the lungs and crucially, their role in asthma and COPD.

Small airways: a key player in the anatomy of healthy lungs

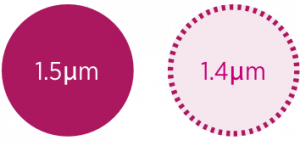

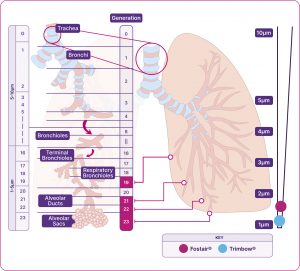

The structure of our respiratory system is critical to how it works. As the trachea branches to two bronchi, which divide again and again into smaller airways, the speed of airflow decreases, and the total cross-sectional area for capturing oxygen increases. This helps ensure there is time for optimal gas exchange with every breath.1,14

All airways can be considered as either large or small, based on size – both are equally important for healthy lung function:12,14

- large airways: the airways that are greater than 2mm in diameter (e.g. the trachea, the bronchi)

- small airways: the airways that lead to alveoli and have a diameter of less than 2mm. (e.g. the bronchioles, the terminal bronchioles, the respiratory bronchioles, and the alveolar ducts and sacs). They are also often called peripheral airways or the ‘silent zone’.12

In both asthma and COPD, the small airways are major sites of inflammation and airflow resistance, affecting normal lung function1,12

The different airways within the respiratory system

Adapted from Usmani et al. 2021.14

Small airway disease (SAD): a common feature of asthma and COPD1,15

SAD is gaining recognition as an important feature in asthma and COPD and is defined as any physiological abnormality seen in the small airways.1,15 The majority of asthma and COPD patients have SAD:14,15,20

- SAD in asthma: in a prospective cohort study (N=773), 91% of patients with asthma had small airways dysfunction

- SAD in COPD: in an observational study (N=202), 93% of patients with symptomatic COPD (CAT score ≥10) had small airways disease.

There is a lack of standard tests to detect SAD, making it hard to accurately detect and quantify it.14,15

Small airway disease in asthma

Asthma affects the whole bronchial tree, including the small airways. It is characterised by hypersensitivity, obstruction and inflammation. Airway obstruction is characterised by the tightening of the airway muscles (bronchoconstriction) and mucus production.2,15,16 Obstruction and inflammation may also trigger myofibroblasts to increase the thickness of the inner walls of the airways, narrowing them further and reducing the area for gas exchange.16

SAD in asthma is associated with:12,15,17

- chronic airway inflammation

- airway remodelling (i.e. changes to the shape/structure of the airways)

- total airflow resistance

- more exacerbations (high vs low SAD scoring group)*

- lower quality of life (QoL) and more frequent healthcare use (high vs low SAD score)

The presence of SAD has been shown to be consistently highest in those with the highest severity of asthma.15

* SAD scores were defined using equation modelling. Participants were then grouped into high or low SAD classes with model-based clustering.15

Small airway disease in COPD

COPD, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is a collective term used for a number of respiratory conditions affecting different areas of the lungs – including emphysema and bronchitis.18 Long-term smoking or long-term exposure to cigarette smoke is the most common cause of COPD, but exposure to other harmful substances can also cause it.1,18

Damage to the cilia in the bronchus is a feature of COPD – this affects the normal clearing of mucus and external substances from the airways; meaning more gets through to lower parts of the lungs.14,19 Additionally, the anatomy and function of the small airways in slowing the airflow may mean they are exposed to any harmful particles for longer periods than larger airways.1

SAD has been an established as a key contributor to airway resistance in COPD for over 50 years.1,14 Evidence for SAD in COPD has been validated in physiological, imaging and histopathological studies.1

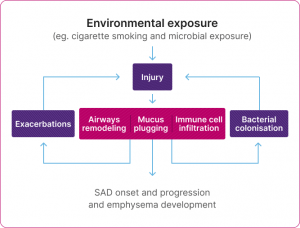

SAD in COPD is associated with:1,14

- immune infiltration in submucosa of small airways (i.e. inflammatory response)

- airway remodelling and wall thickness (i.e. changes to the shape, structure and thickness of the airways)

- mucus plugging (i.e. thick mucus that accumulates in the lungs)

- small airway resistance

- lung hyperinflation (i.e. larger-than-normal lungs, as a result of trapped air)

- poor health.

The cycle of the pathophysiological changes in SAD

Adapted from Usmani et al. 2021.14

SAD is often evident before the onset of symptoms or changes in spirometry or imaging findings in COPD.14

It is suggested that SAD occurs early on in COPD and may happen first, before damage to the alveoli, known as emphysema. It is thought that emphysema may also worsen SAD in return, in a damaging feedback cycle.1,14

Extrafine formulations can reach both large and small airways1,2,3

Both the large and small airways are important targets for the treatment of asthma and COPD. 1,3, 12,15

Treatments for these conditions can differ in both molecule type/class and in molecule size.13,22,21 The size of the particles that deliver medication into the lungs can impact how far they travel and how widely they are dispersed.1,2,3 In general, clinical studies suggest the following distinction:1,2,3

- large particles: can reach oropharynx, trachea, and the upper bronchial branches

- extrafine particles: can reach the whole bronchial tree, including the central and peripheral airways.

Extrafine particles are defined as less than 2μm in mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD), with 1–3μm identified as being potentially compatible with deep lung penetration, in line with airway diameters.13

Airways of the respiratory system

Diagram indicating the MMAD of Fostair® and Trimbow®.

Adapted from Usmani et al. 2021.2,14

Fostair®(beclometasone/formoterol)

Is the only extrafine formulation ICS/LABA combination available in a range of devices and strengths4-7 – designed to reach the large and small airways1,2

Measurements indicate the MMAD.

Trimbow® (beclometasone/formoterol/glycopyrronium)

Is the only extrafine formulation ICS/LABA/LAMA combination available in both a pMDI and NEXThaler8-10 – designed to reach the large and small airways1

Trimbow pMDI 87/5/9 and pMDI 172/5/9

Measurement indicates the MMAD.

* Average particles size of all three components (ICS/LABA/LAMA).8-10

The importance of finding the right inhaler for each patient23

Many other factors, beyond formulation, can affect how well a treatment is delivered throughout the large and small airways in the lungs.23 Other factors that could have an impact on the success of a patient’s treatment include:2,12,23-25

- device type, including the use of multiple vs single inhaler devices

- patient age (also impaired cognition, coordination, and morbidity)

- improper inhaler technique (related to a 50% increased risk of hospitalisation in COPD)

- appropriate training in the use of inhaler device.

When choosing an inhaler with a patient, it is important to consider their preferences, lung function and their inhaler technique.23 A suitable device can improve adherence, health outcomes and QoL.21 An inappropriate one may lead to poor health outcomes and increased risk of exacerbations.23,25-27

Our Patient Support and Education and Events pages include expert videos and action plans to help you support patients with their technique and adherence.